TYPES OF HINGES

V. Ryan © 2002-2008

A large variety of hinges are available from most hardware stores. The type bought depends on how it is to used and what it is to be fitted to. For example, when selecting a hinge for a jewellery box, a small brass butt hinge is likely to be used rather than a concealed hinge. Furthermore, brass hinges are more expensive than steel ones and they give a quality look to the completed product. Below are some of the more popular hinges that are available.

| |||

| BUTT HINGE: Comes in a range of sizes from 13mm to 150mm and is normally used for cabinet doors. They are very strong but cannot be adjusted once they are fitted. | |||

|  |  | |

| BUTTERFLY HINGE: This is often used on light-weight doors and different shapes and patterns are available. They are generally easy to fit. | |||

|  |  | |

FLUSH HINGE: This type of hinge does not require a recess to be cut. They are not as strong as butt hinges but can be used for light-weight doors and small box construction.

| |||

|  |  | |

| BARREL HINGE: This comes in two parts. The threaded part of the hinge is screwed into a pre-drilled hole. They are easy to fit and the hinge can be dismantled. | |||

|  |  | |

| ` | |||

|  |

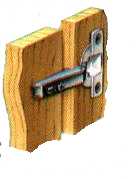

CONCEALED HINGE: These normally come in two sizes (25mm and 36mm. The hinge is adjustable once fitted and is designed with chipboard and MDF in mind.

| |

CONTINUOUS or PIANO HINGE

| |||

| |||

|  |

This is a hinge that comes in different lengths and can be bought in brass or steel. It is ideal where a long hinge is required such as a desk top or a cupboard door. Small countersink screws are normally used to fix it in position.

| |